JAGO - Sculpture beyond borders

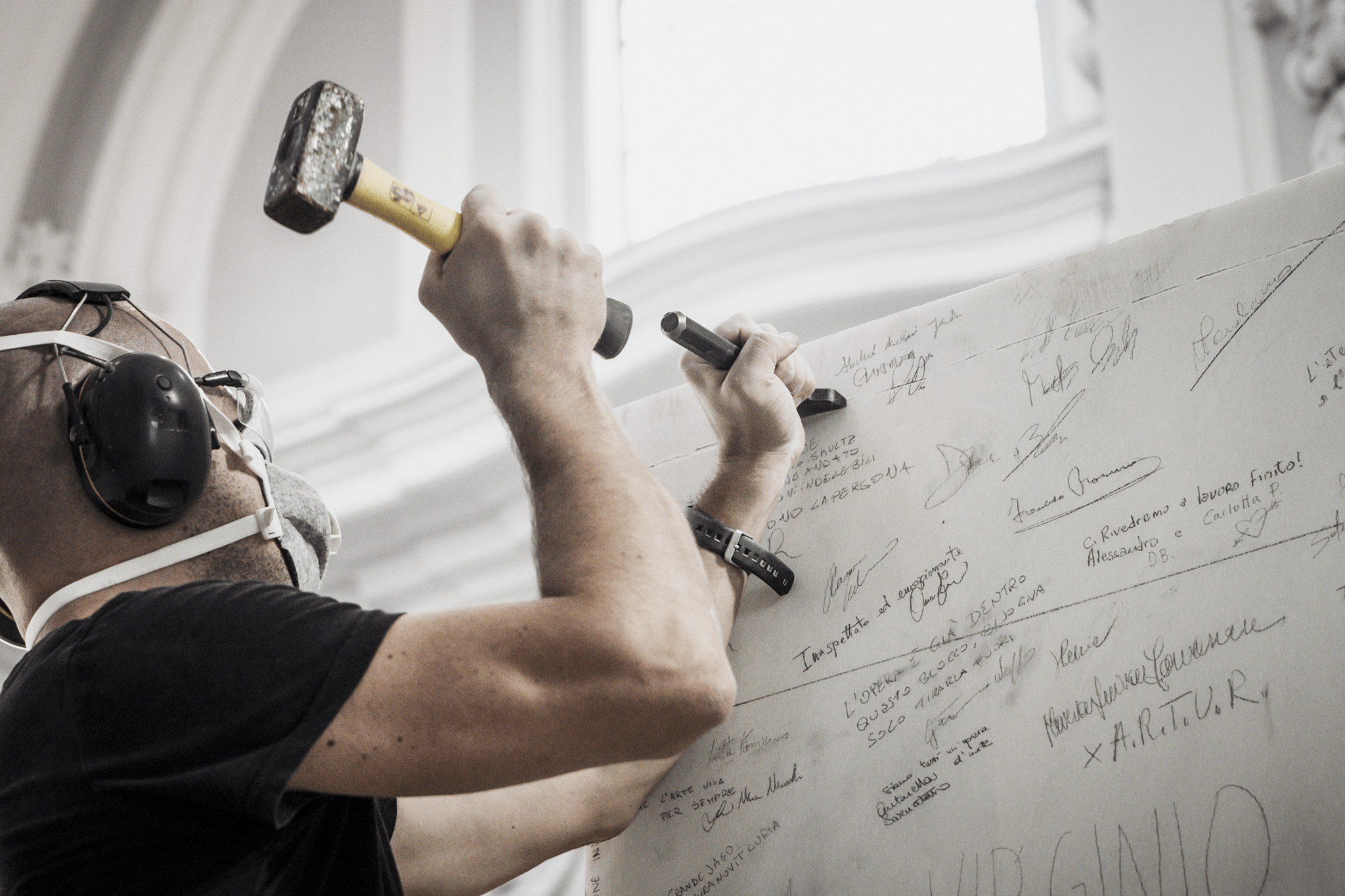

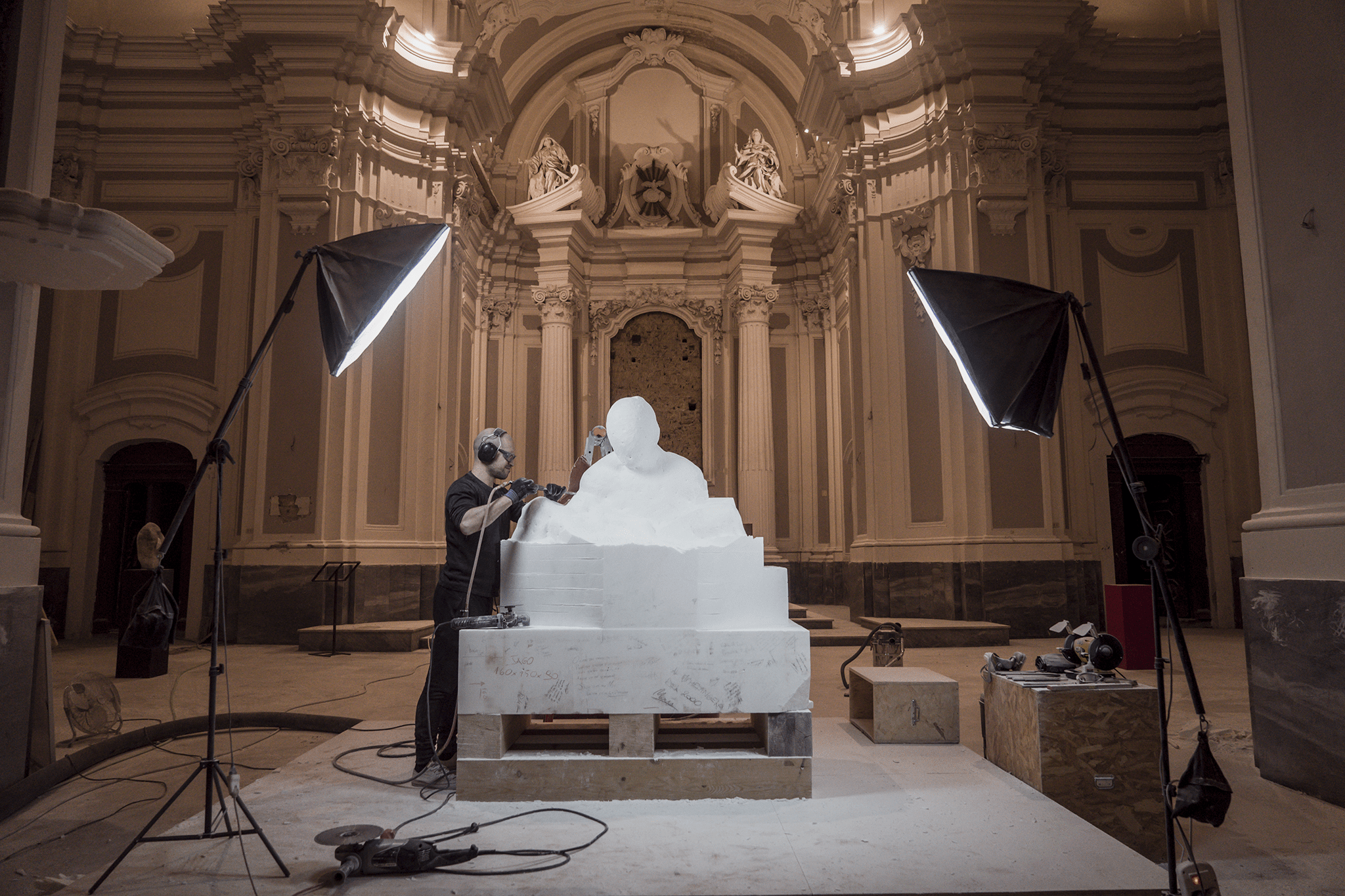

JAGO, born Jacopo Cardillo, is an exceptionally talented sculptor and, despite his young age, one of the most successful contemporary Italian artists at international level. He was born in Frosinone in 1987, where he attended art high school and then the Academy of Fine Arts until 2010. He has lived and worked in Italy, China, Greece and the United States. He was a visiting professor at the New York Academy of Art where, in 2018, he gave a masterclass and a lecture. He has received numerous national and international awards such as the Pontifical Medal in 2010, the Gala de l'Art prize of Monte Carlo in 2013, the Pio Catel award in 2015, the Arte Fiera audience award in 2017. He has also received the investiture as Mastro della Pietra at MarmoMac in 2017. At the age of 24, presented by art historian Maria Teresa Benedetti, he was selected by prof. Vittorio Sgarbi to participate in the 54th edition of the Venice Biennale, exhibiting the marble bust of Pope Benedict XVI (2009) which earned him the aforementioned Pontifical Medal. This youthful sculpture was then reworked in 2016, taking the name of Habemus Hominem and becoming one of his most significant works. It depicts the disrobing of the Pope emeritus and was exhibited in Rome, in 2018, at the Carlo Bilotti Museum in Villa Borghese, with a record number of visitors (more than 3500 during the inauguration alone). In 2019, on the occasion of the European Space Agency's Beyond mission, Jago was the first artist to send a marble sculpture to the International Space Station. The work, entitled The First Baby, and depicting the fetus of a child, returned to earth in February 2020 under the custody of the head of mission, Luca Parmitano. Since May 2020 Jago has resided in Naples, where he works in his studio at the Church of Sant’Aspreno ai Crociferi and where, at the beginning of November of the same year, he created the installation Look Down, in Piazza del Plebiscito. We met him during the exhibition of his Pietà at the Church of the Artists (Santa Maria in Montesanto) in Piazza del Popolo, Rome.

Look Down, Piazza del Plebiscito in Naples

Jago, in your biography it is mentioned that you are involved in sculpture, graphics and video production. We know you above all as a sculptor. Can you tell us a little more about your graphic and video productions?

For fifteen years, since I started working for myself and becoming independent, I have wanted to complete my works by providing them with graphic, musical and video support to translate the sculptural value into a form that can be used by more people. Rather than graphics or video production, therefore, I would simply speak of "communication".

You are originally from Ciociaria but your studio is in Naples. Where did this choice come from?

It has been a long way. I was born in Frosinone and raised in Anagni, where I continue to have a small studio in the cathedral square, in front of Palazzo Bonifacio. There, I made most of my works, until I felt the need to ‘grow up’, go and discover the world. Naples has been a recent choice, after repeated trips to China and after living in Greece and Verona, where I created several works. I also spent two years in New York, living in Manhattan and working on Long Island. The Veiled Son was born in New York, the last stop before landing in Naples, inaugurated at the end of 2019 at the Sanità. During my presence in Naples, I have felt the necessity to build something: Naples is a fertile ground and artists can give shape to their ideas only where there is a fertile ground and the necessary space for them to grow. I spent sixteen months in the city, during which I work at the Pietà, currently exhibited here in Piazza del Popolo, but now I'm about to move to Rome. In fact, my presence in Naples was not intended so that I could have a studio in a beautiful church, but rather to redevelop the place through my presence, which is quite different. It means to take an abandoned place and allow the conditions for its redevelopment. Giving it back to the public perhaps in a different form, like a museum, is an operation I wanted to dedicate myself to, and it has been successful. Therefore, once my mission in that context was completed, it no longer made sense for me to stop there. The goal now is to move to another place in order to make new works. From December, therefore, I will be in Rome.

You mentioned your stays in Greece, China, the United States. What did those experiences have left you, considering that the contexts are certainly very different from Italy?

They have all been very formative experiences. For a long time, I thought that travel was not important from the point of view of training. Then I realized the richness in getting to know other cultures, and in listening, because knowing each other also means knowing how to listen. You can't communicate if you don't know how to listen. I can say that I came out renewed, grown-up, after each of these experiences, because they all came from the desire to get involved. In this sense, I discovered that I was a container to be filled: that I was really very empty. Today I know how much empty space I continue to have inside of me. The more things I add, the emptier that space remains. I want to use the time of my life to improve myself and I know that these kinds of experiences can be the best school.

The sculptural work that launched you, at the age of 24, is the marble bust of Pope Benedict XVI. How did the idea of casting his figure come about? What did inspire you about him?

The pope is a controversial figure. His role is also very interesting. Speaking from the human point of view, I don't think it's easy to put on those clothes. We all know what happened, in this specific case, to Benedict XVI. In that figure, therefore, there is a strong human component. The work was commissioned to me, but at first it was not accepted because I interpreted it by piercing his eyes. I would call this "opening the eyes", but that was my aesthetic interpretation, a celebration of an artist I love deeply, a great master of the tradition called Adolfo Wildt, teacher - among other things - also of Lucio Fontana in Brera. The work, I said, was not accepted. They proposed to fill his eyes and I refused. I was really stubborn. Fortunately, however, it went well because, afterward, it was exhibited at the Royal Palace of Caserta and at Palazzo Venezia, in what was then called “La biennale di Sgarbi. The state of the art". After that, it was rewarded by the pope with the pontifical medal and it obtained a whole series of awards which, to tell you the truth, are of little interest to me but which, in any case, give courage to a young man who takes his first steps into art. Over time, we put certain things in the right place, and they become simple knick-knacks. The very day we were dismantling my personal exhibition, my father sent me a message telling me that Pope Benedict had renounced his pontificate. At that point, I understood that I had the opportunity to intervene in something that was happening at that precise historical moment. If the pope had died, my work would have remained an institutional portrait, without any particularly distinctive features, and of which I was not even too proud. Instead, that event gave me the opportunity to get back to it. The transformation was important in terms of meaning, for two reasons: first of all, because I shot a video that showed the process of making it - the so-called "dispossession" - turning it, therefore, into something interesting from a narrative point of view and recognising, more or less consciously, that the gesture itself could be work. The video is a work of art as well, and it has value because what had happened is told through the video. Consequently, every gesture that led to the completion of the work has become valuable. The second reason is more personal because I had to deal with the destruction of something that had won awards: those same awards that - as I said a moment ago - have no other use than getting dusty on the shelf. This aspect was, perhaps, the most important: destroying my attachment to a value, to a material good that actually had to move away from me. From that moment on, everything changed, because my attachment to the things I make has drastically decreased. I realized that I had to stop being afraid of losing something. We don't really lose anything. Things simply transform.

Habemus Hominem (2009- 2016)

Your New York period was marked by another very significant work: "The Veiled Son", inspired by the Veiled Christ of Sanmartino. What attracted you to this late Baroque masterpiece?

I have absolute reference points which are the ones in which I recognised myself from an early age. Faced with certain works, I said to myself: “this is a language that I understand, I feel good in following this path”. I therefore preferred to be inspired by those masters who have left values so engraved into our society that they have become global linguistic references. There are masterpieces for which we are famous all over the world. We are not certainly known for the nails hanging on the wall or for the ladybugs printed with the peace flag, but for the Colosseum and for all those works that have become part of the collective vocabulary of our emotions. Today we use those values as terms of comparison when we move around the world, to measure what is beautiful and what is ugly, what must be preserved, what we can put aside, how to behave. I recognise myself under certain parameters. Then, it is not a problem for me that an artist recognises himself as such, that a community also likes him and that he creates the ladybug on the wall but, simply, it does not concern me. It may well be that I like that artist, that I buy his work, but that's another story.

Your artistic path has its roots in the techniques used by the masters of the Renaissance but, at the same time, it largely uses modern social networks to create a direct connection with the public. Hence, a blend of past and present that has proved to be a winner. What is the next step?

There is neither past nor present nor future, only the things we do. Where is it written that marble should be part of the past only because it was used by the artists of the past? Why can't we consider it a contemporary material? Why can't I speak that language if it is my language? And yet, if at the inauguration of this exhibition four thousand young people showed up in an orderly manner, wearing face masks, carrying the Green Pass certificate, and couldn't wait to get in and see my work up close, I should say that I speak a language that young people understand. And understand it well.

How would you describe your relationship with the public? For example, you regularly engage in workshops, masterclasses and university lectures. Do you find this direct interaction to have beneficial effects on your work?

My audience and I are a team. I follow the people who follow me: it is an exchange. People choose to follow what I do because I provide them with content about them. I don't always manage to interact directly but I see whatever happens, and I read all the comments that come to me. Then, maybe I don't have time to reply, because by now a mechanism has been set in motion and it is very difficult to manage it, but I have the situation absolutely under control and this gives me great energy: the comments that come, the different points of view, criticisms are invaluable. Do you know how many people criticize me, but with love, respect, and passion? Those are the things that help me mature. I don't think I know everything, I can only share what I have experienced.

In 2019 you were the first artist to send a marble sculpture (The First Baby) to the International Space Station, on the occasion of the European Space Agency's “Beyond” mission. What was the purpose of the initiative?

In reality, that for me was another small proof that if you really want something, you can get it. I am speaking, of course, about the experience, not the result in terms of audience or applause. Even if no one had noticed, I could have shown myself that I was able to transform an idea, a thought, into reality. How much, such a thing, help us grow? I try to surround myself only with people who encourage me, who participate positively. Negativity does not concern me. It exists anyway, regardless. I see that. The only thing that interests me about that is having clear that I can succeed in the enterprise, in a good way. I could go deeper, I could talk about every single phase of the project, focus on the knowledge, the path, the difficulties, but this would not add and would not take anything away from the experience. After all, all our innovation consists in doing something that was not done before. Once done, things become normal, but to get to them, you have to go through an endless series of detractors.

One thing I can add about The First Baby is that it's not a masterpiece, it's nothing incredible. The incredible thing is where it traveled, the journey it made, with the person who took it with him, arriving at a place - the international space station - that is a perfect replica of the Earth. That is the real masterpiece: a masterpiece that is the fruit of collective genius and intelligence, of people who have dedicated their lives to research and who, by putting their genes together, have managed to create this miracle, which today makes us dream, gives us a new perspective. How much is my work worth compared to that? Nothing? Well, maybe a speck. I compare it to one of those little grains of sand that participates in the work of all the other grains of sand that give us the beautiful scenery of our beaches.

At the moment you are in Piazza del Popolo, in Rome, where your “Pietà” is on display. In addition to showing great knowledge of anatomy, many of your works seem to link up with the combination of art and religion that has always accompanied Italian artistic production. How important is the spiritual element for you?

I have always been interested in anatomy. It is a universal language that everyone can understand. With regard to spirituality, it may seem that my works have a relationship with religion, but this is not the case. I have never made any work motivated by religious reasons. I have used a language that is in line with a word in our emotional vocabulary that has already been used or that someone has coined, and that is another matter, but in fact, my work does not contain any religious element. Even the place (in this case a church) was chosen for the beauty of the place itself, because our Christian tradition has surrounded us with magnificence - thanks to great investors and patrons - and, in my opinion, it is still the churches that hold the primacy in terms of beauty. I like to exhibit my works in these sacred environments, but religiosity is a personal fact. My Pietà can be seen by a Muslim, a Christian, a layman, and each of them can see himself again. Everyone experiences art freely, based on the emotions he or she feels, that's the beauty. There is certainly spirituality in what I do, but while I am doing it. My work must not be saturated with spirituality, otherwise I would limit its communicative capacity only to those who deal with spirituality or to those who understand it, and this does not want to be my message. What interests me, however, is that it can be enriched by the spirituality of others and the religiosity of others, or by the absence of both. The simple act of working on a certain piece is for me a moment of meditation, in which I become one with what I do, but it is something that remains limited to that particular moment.

Is there a project that you have not yet completed but which you aspire to? A dream in the drawer?

There is always a new dream to be realized. I live my life in a planning way: I get up in the morning with a purpose and this gives me direction. A friend of mine once told me: "the person is lucky and happy when he wakes up with a purpose". I build my intentions from time to time. I always set myself new goals, which concern my personal growth and improvement. To do this, I get involved in an area that I know, I speak a language that I understand and I love to share my things and to come together with those who recognise themselves in what I do. I do not pretend to impose myself. I do what I have to do, without any expectations but with the conscience of those who want to aim high. Everything, then, reaches its natural dimension, independently.

In the cover: The Pietà

Images courtesy of the artist (www.jago.art)