DRIVE MY CAR – Murakami's tale of loneliness and hope

As the first scenes of Drive My Car unravelled, I thought ‘Yes, this is definitely something Murakami would write about…’ and yet, it was not. What happened in the film opening, was a very original and welcomed ‘addition’ to Haruki Murakami’s short story that bears the same name.

Haruki Murakami’s Italian version of Men without Women – a collection of short stories including Drive My Car – sat on my bookshelf for some time, but I hadn’t read it yet. So, for once, I decided to approach the movie first. I loved how the screen adaptation added layers to Murakami’s detailed but less intriguing plot. It is not surprising that Drive My Car is a contender for the 2022 Oscar nominations not only for Best International Feature but also for Best Picture.

Once the movie ended and my reading of the short story too, I realised that I liked the film better. It is difficult, normally, to condense a whole literary work into a movie, and that is why we are often disappointed by screenplays. But this time the film, directed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi (who co-wrote the screenplay with Takamasa Oe) does a great job in adapting Murakami’s style, in which details and dialogue play an important role. Yet, Hamaguchi and Oe made the plot much richer, starting from the beginning and then – definitely – towards the ending.

The main character, Yusuke Kafuku (played by Hidetoshi Nishijima) is an actor and theatre director who has a special working partnership with his wife, Oto (Reika Kirishima). Oto is a screenwriter who crafts stories during sex, reciting plot developments to him afterward in an almost trancelike state. Kafuku takes her hints, completes the story and brings it to life. This seems quite an important detail in the otherwise tired relationship between husband and wife – but it’s not found in Murakami’s story.

What comes to be very clear from the start is Kafuku’s loneliness, and his incapability to communicate with his wife for matters not related to their work. Kafuku is unable to bring up her unfaithfulness once he finds out that she is cheating on him (something he is aware of for quite some time in the short story). In the movie, it appears that she feels that her husband knows what’s happening, and she would very much like to draw his attention to it and be part of a conversation that never happens. The sense of remorse for this failure, after the woman’s sudden death, plunges Kafuku into darker and even more solitary moods.

Two years later, Kafuku is in Hiroshima, directing a production of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. Regarding the play Kafuku is preparing, we need to be grateful for the mastery of the two screen players, who add a very important and unusual detail to the Japanese writer’s short story: the actors cast for Uncle Vanya come from different countries, and one of them is deaf-mute. The result is a strange play in different languages, a metaphor for the difficulty of communication among people.

In Hiroshima, Kafuku asks for accommodation away from the theatre because he likes to drive and revise his scripts out loud on cassettes recorded by his wife, but – due to his glaucoma – the theatre management obliges him to have a driver, Misaki Watari (Tōko Miura). Kafuku has never really trusted women behind the wheel, especially of his own car. This scepticism is clearly expressed in the first lines of Murakami’s short story:

“For the most part, women paid closer attention to details, and they listened well. The only problem occurred when he got in a car and found a woman sitting beside him with her hands on the steering wheel. That he found impossible to ignore. Yet he had never voiced his opinion on the matter to anyone. Somehow the topic seemed inappropriate.”

But finally, Kufuku has to admit that Misaki’s driving skills are excellent. The two of them spend much of the film going around the city in Kafuku’s vintage red Saab (originally yellow, in the short story), a bright dot on endless grey roads. Somehow, in the long silences that are part of the driving sequences, they soon form a special bonding, and Kafuku feels more and more comfortable and relaxed in her company, to the point that they start talking about very personal matters. Misaki seems to be able to read Kafuku’s mind. She is a discreet but not detached person with her own heavy emotional baggage. She just does not let any of her feelings transpire until much later. She comes up more approachable than how she is first described – in the original short story – by Oba, the man who works at the garage and who recommends her: “She’s brusque, shoots from the hip when she talks, which isn’t often. And she smokes like a chimney…You’ll see for yourself when you meet her, but she’s not what you’d call cute, either. Almost never smiles, and she’s a bit homely, to be honest.”

Spending more and more time together, both Kafuku and Misaki will be able to come to terms with their own personal traumas. All this happens while Kafuku decides to pick his wife’s lover, Koji Takatsuki (Masaki Okada), as the main actor in the play he is setting up. Takatsuki, despite his very young age, will have to play uncle Vanya, a role normally interpreted by Kafuku himself. Kafuku feels that he can get to know more about Oto through the confessions of this charming young man, thus paying the emotional price for his inability to confront his wife when it was time to do so. Quite remarkable is the scene with powerful close-ups, in which the two men are sitting close to each other in the back seat of the car. The movie plot, once more, swerves from the original story.

Ultimately, the title of the movie (and of the short story) condenses – in a nutshell – what the plot is about: driving endless hours in a space where Kufuku can feel safe and taken care of, and where Misaki can do what she is able to do best to put aside the haunting ghosts of the past: driving.

Murakami’s story is very much anchored to details, and the omniscient narrator describes them with great attention. Very central are – like in the movie – the dialogues, which sustain the entire plot: dialogues between husband and wife, Kafuku and Misaki, and between Kafuku and Takatsuki (Oto’s lover). This encounter is particularly important for Kafuku, as it allows him to deal with his regrets: his knowing about his wife’s unfaithfulness without reacting to it, and the realisation that his life has been only a continuous ‘acting’.

“Smiling calmly when his heart was torn and his insides were bleeding. Behaving as if everything was fine while the two of them took care of the daily chores, chatted, made love at night. This was not something that a normal person could pull off. But Kafuku was a professional actor. Shedding his self, his flesh and blood, in order to inhabit a role was his calling. And he embraced this one with all his might. A role performed without an audience.”

In the movie, all this is left to our observation of Kafuku’s often blank and poker-face expression, his apathy, his pretending to live a normal life with his wife, and the trauma of a loss that – earlier in their married life – had greatly contributed to straining their relationship. Kafuku knows that his life has been a continuous impersonation of different roles, exactly like his job.

When Misaki tries to guess why he wanted to be an actor, asking

“You loved being someone other than yourself?”

He replies:

“Yes, as long as I knew I could go back.”

“Did you ever not want to go back?”

Kafuku thought for a moment. No one had asked him that before […]

“There’s no other place to go back to, is there?” Kafuku said.

It will be hard, but thanks to Misaki’s help, he will – finally – ‘go back’, and their personal journeys of atonement and healing are very well developed in this excellent movie.

The characters are the soul of Drive my Car. Through their evolution, the close-ups, the long moments of silence in a three-hour movie that never feels too long, Hamaguchi displays the power of language, loneliness, love, the inability to accept one’s past, and people’s vulnerability when sharing it with others.

(The passages quoted in the article are taken from the short story 'Drive My Car' - 'Men without Women', Knopf, 2017. Translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen)

Link to the article in Italian here

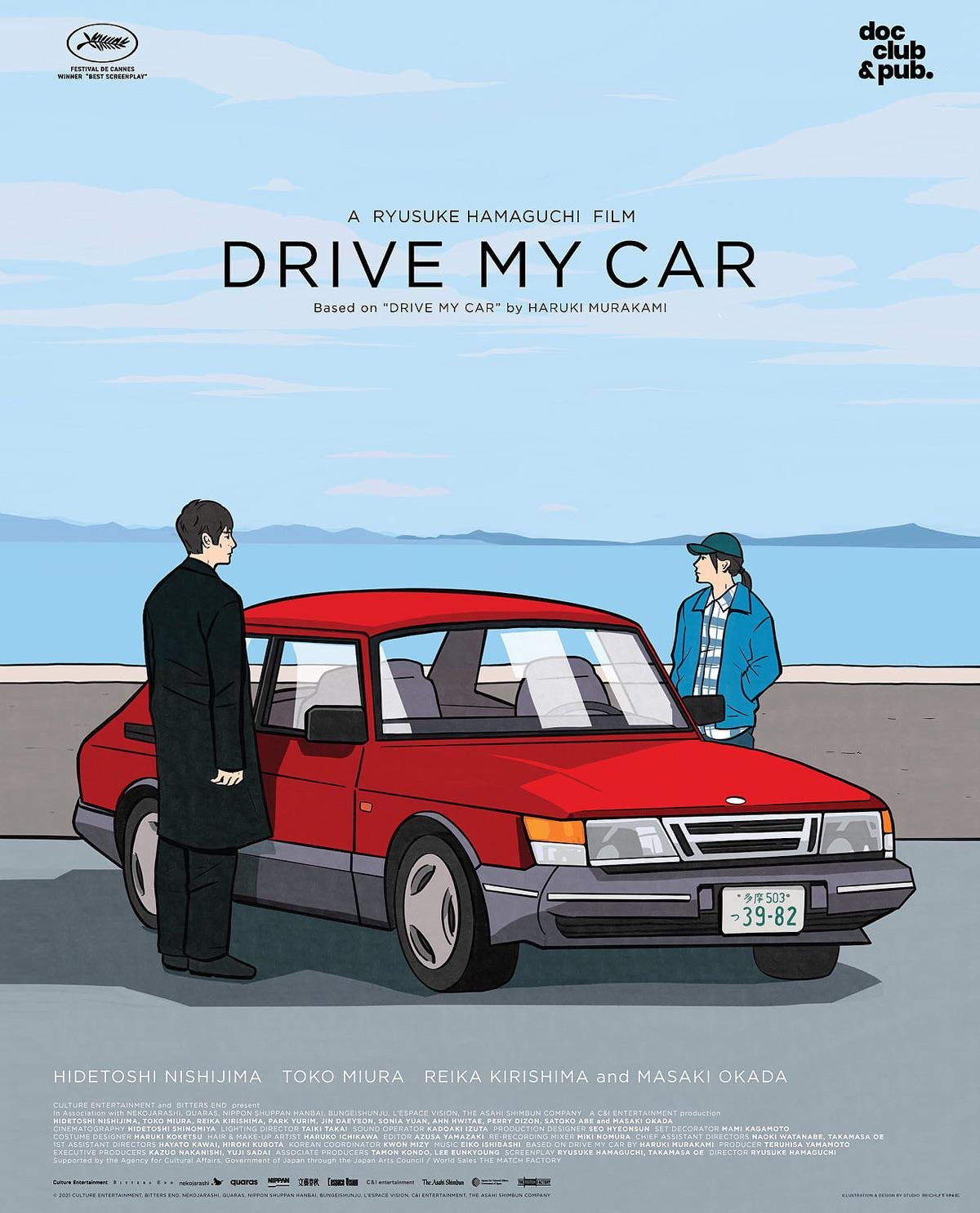

Cover:

Image taken from the film poster