IKEBANA - Timeless compositions

Ikebana, the Japanese art of arranging flowers, branches, stems, and leaves in vases, best embodies the concepts of wabi-sabi and mono no aware, creating harmony among lines, colours and space.

Wabi-sabi (侘び寂び), which combines wabi (“less is more”) and sabi (“attentive melancholy”), celebrates impermanence, incompleteness, and imperfection. Mono no aware (物の哀れ), literally “the pathos of things,” expresses the aesthetic appreciation of transience. With its elegant yet ephemeral compositions, ikebana — literally “arranging flowers and bringing them to life” — evokes a sense of beauty permeated by a sweet melancholy for what is destined to fade, using only a few natural elements such as flowers, branches and leaves.

In Japan, however, beauty is never purely aesthetics: it encompasses a profound philosophy of life. Ikebana is a meditative art in which every element – size, position, colour combinations, and the material of the vase – carries meaning and contributes to conveying harmony. Creating ikebana requires reflection, calm, and a deep connection with nature and its seasons —an act of mindfulness, to use a modern term.

Originating in the 6th century AD as a Buddhist religious offering and act of devotion, brought to Japan via China and Korea, ikebana evolved during the Muromachi period (1333-1573), when it took on a more defined structure, integrating the expressive use of leaves, as well as flowers.

Fascinated by this art form during my long stay in the Far East and always eager to deepen my understanding of Eastern philosophy, I recently attended the event Timeless Harmonies - Ikebana between tradition and modernity at MUDEC in Milan, organised by the Garden Club Milano. The exhibition and demonstration, led by Grand Master Satoshi Hirota of the Ohara School, featured precious vases from the museum's Japanese collection — including some from the Meiji and Edo periods. The event celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Garden Club Milano and tenth anniversary of its collaboration with MUDEC.

Founded in the late 19th century by Unshin Ohara, the Ohara School stands out for its dialogue with the West, in contrast to traditional ikebana. Its moribana style, characterised by landscape compositions in wide, shallow containers, reflects this openness.

Among Master Hirota’s compositions, I particularly appreciated a landscape arrangement: a large branch with red berries emerging from a twisted trunk, surrounded by ferns, leaves, and other berries, evoking a corner of the forest. Beside it, a low container represented a pond, with two irises sprouting from dense greenery, reproducing the vegetation along the banks. This composition was in the bunjin style (bunjinga: 文人畫 “painting by intellectuals”), a form of Japanese floral art inspired by the spirit of Chinese scholars, poets and artists of the 17th and 18th centuries, which placed particular emphasis on the connection with nature.

Another memorable arrangement combined two orchid branches, areca palm, seed pods, magnolia leaves, and branches with small pomegranates in a brass vase with dragon-shaped handles. The colours – green, pink, yellow and orange – intertwined gracefully.

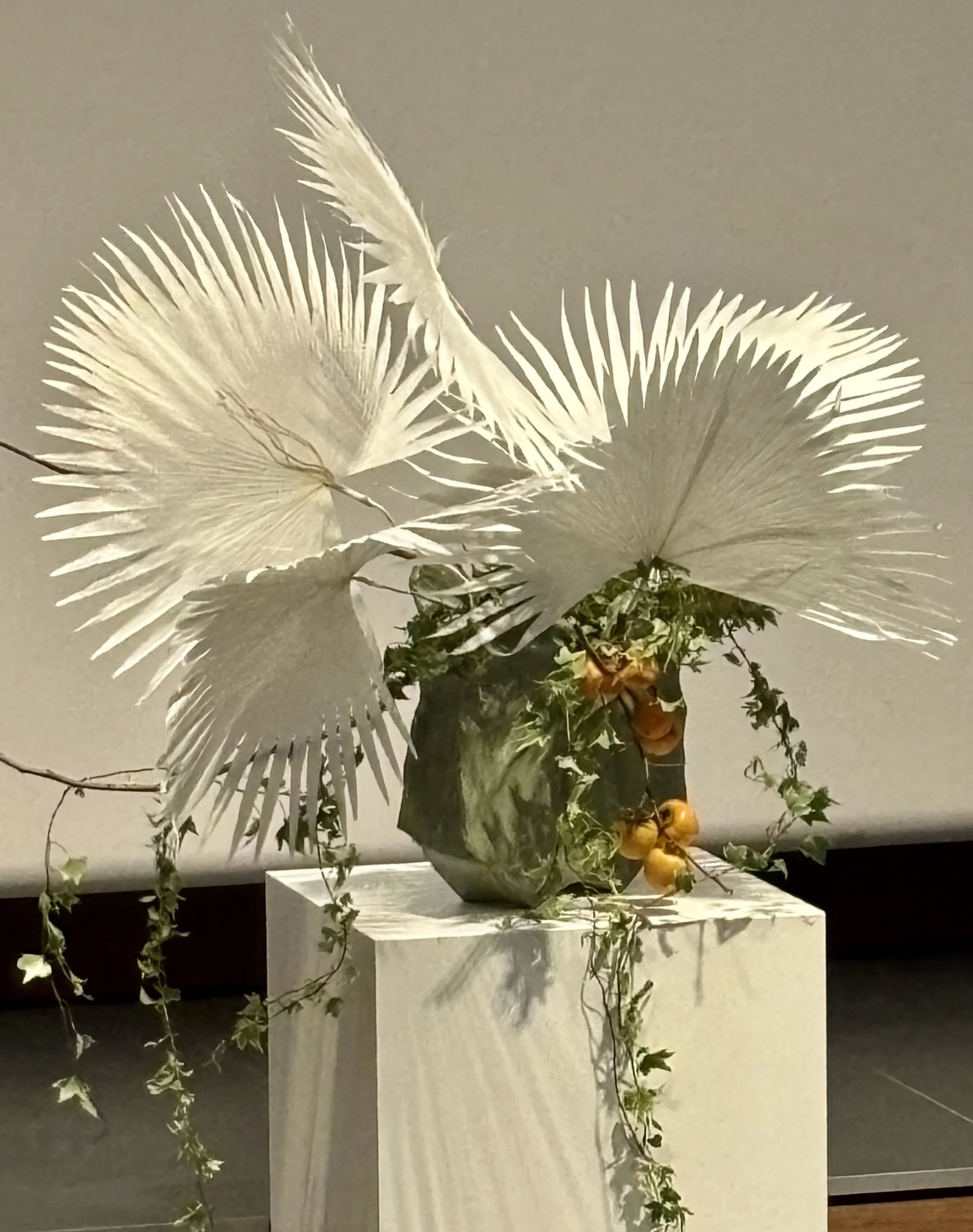

Equally striking was an arrangement in a square, irregular green ceramic vase, enriched with ivy, persimmons, and bleached palm leaves, which created an ethereal, almost transcendental effect.

Among the other works – one of them with hydrangeas, forsythia, and branches spilling out from the sides of the vase, creating flow and movement – the final piece was imposing. In two tall, elaborately decorated bronze vases, the Master placed pine branches, red berries, yellow and pink protea, and an auspicious element consisting of a bamboo cane adorned with thin threads of silver and gold paper, typical of certain Japanese celebrations. The powerful elegance of this work enchanted the audience.

With his 30 years of experience, Grand Master Hirota created these compositions with magical spontaneity, as if guided by spiritual inspiration, without ever touching the vases. Right outside the auditorium, another MUDEC exhibition space had been enriched with his creations for “Japan Days - Waiting for the Snow”, which completed this immersive experience.

During Timeless Harmonies, I felt as if I had been transported into the silence of a Japanese tea house, inside a neat park, surrounded by simple yet deeply refined natural beauty. Ikebana reminds us that everything is transient, yet our connection with nature remains eternal and memorable.

茶の花に / あたたかき日の / しまひかな

(Cha no hana ni / atatakiki hi no / shimahi kana)

A tea flower, the warm days are coming to an end

Takahama Kyoshi (1874-1959)

For more information on ikebana, related events, and courses, visit the Garden Club Milano website. You will also discover the history of the association, founded in the 1960s by Jenny Banti Pereira, a pioneer in spreading ikebana throughout Europe and Italy.