SEBASTIÃO SALGADO’S ‘AMAZÔNIA’ – A photographic journey through the world’s richest ecosystem

On a sultry August afternoon, I found myself in the thick of the Amazon Forest. The trees were imposing, with lush leaves cascading down like waterfalls, trunks shooting up the sky, and lianas dangling like snakes. The sounds of the forest, the roar of water tumbling from high, and the call of unknown birds, insects, and other mysterious creatures, accompanied my hesitant steps. I was scared at first, not knowing what to expect from this mythical place, crossed by a majestic river, its equally large tributaries, and home to the largest freshwater archipelago, the Anavilhanas – its island rising and then disappearing from the dark waters of Rio Negro. Suddenly, I heard some voices, far away, and a gentle singing, closer and closer. Curious faces were staring at me…

Korubo family. Amazonas, Brazil, 2017

If I close my eyes, I’m still there, revelling in the multi-sensorial experience of Amazônia, an exhibition of photographs by Sebastião Salgado – accompanied by the specially commissioned soundtrack composed by Jean-Michel Jarre – held at the ‘Fabbrica del Vapore’ in Milan - extended until 28 January 2024.

The Amazon’s surface is ten times the size of France. And yet, vast areas of this territory – 60% of which is part of Brazil – have been destroyed and are being destroyed daily. Of the original indigenous population of five million people (in the XVI century), only 370,000 are left today, and their existence is in constant danger.

Viewing the more than 200 photographs taken by Salgado by land, water, and air over a period of seven years, and portraying vegetation, rivers, mountains, and people of the Brazilian Amazon Forest, was a total immersion into a magical land, and a great educational experience. I discovered, among other facts, that of the 188 indigenous groups still living in the forest and speaking 150 different languages, 144 of them have never been contacted.

The destructive power of man over this precious forest is well-known: deforestation, logging, gold mining, cattle ranches, and soybean plantations taking over indigenous lands. Only the impenetrability of the jungle has allowed some of the ethnic groups to keep their traditions. And so, I start to delve deeper into the secret heart of the “Forest”.

The first exhibit found upon entering is a series of brass plates, part of “Amazônia Touch”, designed for blind and visually impaired people. The twenty-one panels allow visitors to read through touching and have been conceived with Foundation Visio – an organisation dedicated to opening access to cultural activities for the visually impaired.

From there, one can move right or left, just as if they were exploring the forest.

Anavilhanas islands, Río Negro. Amazonas, Brazil, 2009

The big black-and-white pictures of vegetation, rivers, animals, and landscapes hang at different heights and immediately capture the visitors, drawing them into an otherworldly dimension. Interspersed in the wide hall are spaces that reproduce the local ‘ocas’, the indigenous houses. Each of them tells the story of a specific tribe: the Amazon Forest is also made up of the people who daily depend on it, the very first inhabitants of this region, who live in the heart of the jungle.

I visited each ‘oca’ driven by the curiosity to learn about the various indigenous, accompanied by the real sounds of the forest, courtesy of Jarre’s hypnotising music: animal calls, leaves rustling, water falling and birds singing. I also watched projections and listened to the native people speak about their plight in an overdeveloped world where money and power rule all.

Moving from one photo to the next, from one tribe to another, I witnessed their peculiar customs and traditions, including some unusual ones. The Suruwahá, for instance, is a tribe still hunting with poison-tipped arrows, and has a high death rate due to the tradition of ingesting timbó, a very toxic substance normally used to stun prey in fishing. And yet, within their community, there is acceptance of this way of dying, which is in accordance with their cosmology.

The pictures of the women belonging to different tribes are the ones I still most vividly remember. I was mesmerised by the elaborate tiaras worn by the women of the Zo’é tribe, made with white feathers from king vultures. The Zo’é is also the only indigenous people in Brazil wearing the ‘poturu’, a wooden labret placed under the lower lip.

I then stopped in front of the picture of a girl, Ino Tamashavo Marubo, of the Marubo tribe, wearing several necklaces made of white shells from river snails that passed through her nose and fell down her body. A parakeet grips her thumb. There is the custom, among the indigenous people, to raise baby birds and the young of animals they have hunted as pets, as if they were their family members.

Another girl, from the Yanomami indigenous territory, has thin, sharp, pointed pieces of wood piercing the area around her mouth and her nostrils.

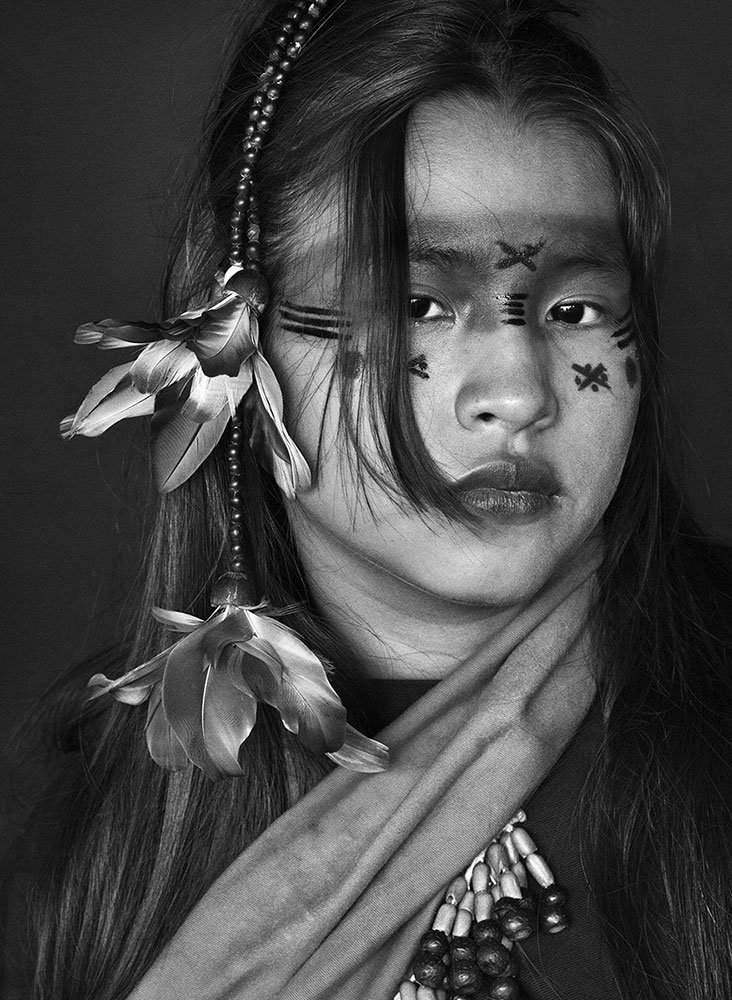

Yara Asháninka (Kampa do Rio Amônea Indigenous Territory), appearing also on the posters of this photographic exhibition, bears ornaments made of seeds and feathers and has small designs painted on her face, indicating that she’s not yet engaged. While Luísa, from the same group, dressed in black with adorned hair and an elaborate bracelet on her wrist, sits elegantly as she holds a mirror and paints her face.

For this project, Salgado was improvising photo sets in different ‘corners’ of the jungle, just using a large black tarp as a background. But for the indigenous people, photo taking was a unique occasion, and they always wanted to appear well-groomed and at their best.

There are stories of sacrifices, exploitation, and recovery too, among the tribes visited by Salgado, as is the case of the Yawanawá. In the 1970s, their community numbered only 120. Stricken by alcoholism due to abrupt changes to their way of life, treated as slaves by the owners of rubber plantations, and forced to give up their language and their rites to worship Christianity, the Yawanawá were bound to go extinct. When Bira became the leader of their group, in the early 1990s, he expelled the missionaries and brought back the teaching of the old language and the Yawanawá myths. The population grew to 1200 and is living proof of the possible cohabitation of old traditions (among which their striking ‘feather art’, as you can see in the cover photo) with the contemporary world.

Salgado has been involved in numerous humanitarian projects during his career as a photographer. Together with his wife Lélia Wanick Salgado, responsible for the curatorship and scenography of the exhibition, he founded The Instituto Terra Project, aimed at restoring part of the Atlantic Forest in Brazil, in the Rio Doce Valley of the state of Minas Gerais. In 1998, Sebastião and Lélia turned this land into a nature reserve. The Instituto Terra is dedicated to a mission of reforestation, conservation, and environmental education. It also developed a water conservation project.

Before leaving the exhibition, I read Salgado’s biography. Winner of numerous honours and prizes, member of various art and literary academies, UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador, founder of nature conservation projects, he travelled to over 100 countries – in his early career, in particular, to those mostly stricken by poverty, famine and wars.

Once back home, I watched The Salt of the Earth, a docufilm about Salgado’s life, co-directed by Wim Wenders and the photographer’s son Juliano Ribeiro Salgado – which received the Special Prize at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival. It is a faithful portrait of the ‘man’ behind the camera; of the psychological consequences of reporting about war and famine; of the loss of faith in the goodness of human nature; and of the sacrifices his family went through during his long and frequent photographic expeditions far from home.

I’m still under the spell of Amazônia and I can assure Lélia that – for me – what she wished for the visitors came true: Amazônia is “an intimate experience that stays with them long after they have left the exhibition”.

Mariuá Archipelago, Rio Negro. Amazonas, Brazil, 2019

In partnership with Instituto Terra, this project has the aim of planting 1 million seedlings of 120 endemic species over 8 years, supporting the healthy growth of the native forest. The project will cover a total area of 700 hectares (1,730 acres) of land and will ensure the self-sufficiency and bio-diversity of the forest for the next decades. Click here for more information about this exhibition.

PHOTO CREDITS

In the cover: Yawanawá girl. Acre, Brazil, 2016

© Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto

Gallery: Ashaninka girl. Acre, Brazil, 2016 (left)

Yara Ashaninka, Kampa do Rio Amônea, Acre, Brazil, 2016 (right)

© Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto

Images: salgadoamazonia.it

© Sebastião Salgado/Contrasto